JONKER Adolph

Adolph Jonker

There has been much controversy for over 2 centuries regarding the origin of stamvader Adolph Jonker.

Since the late 18th century Adolph Jonker has been mentioned by numerous authors and several theories emerged, but all without conclusive evidence to back them up fully:

• 1772: Naturalist Sparrman indicated Adolph was of mixed race, his mother being non-European

• 1902-1954: Historians Colenbrander, Moritz and Redelinghuys indicated that Adolph was of German descent

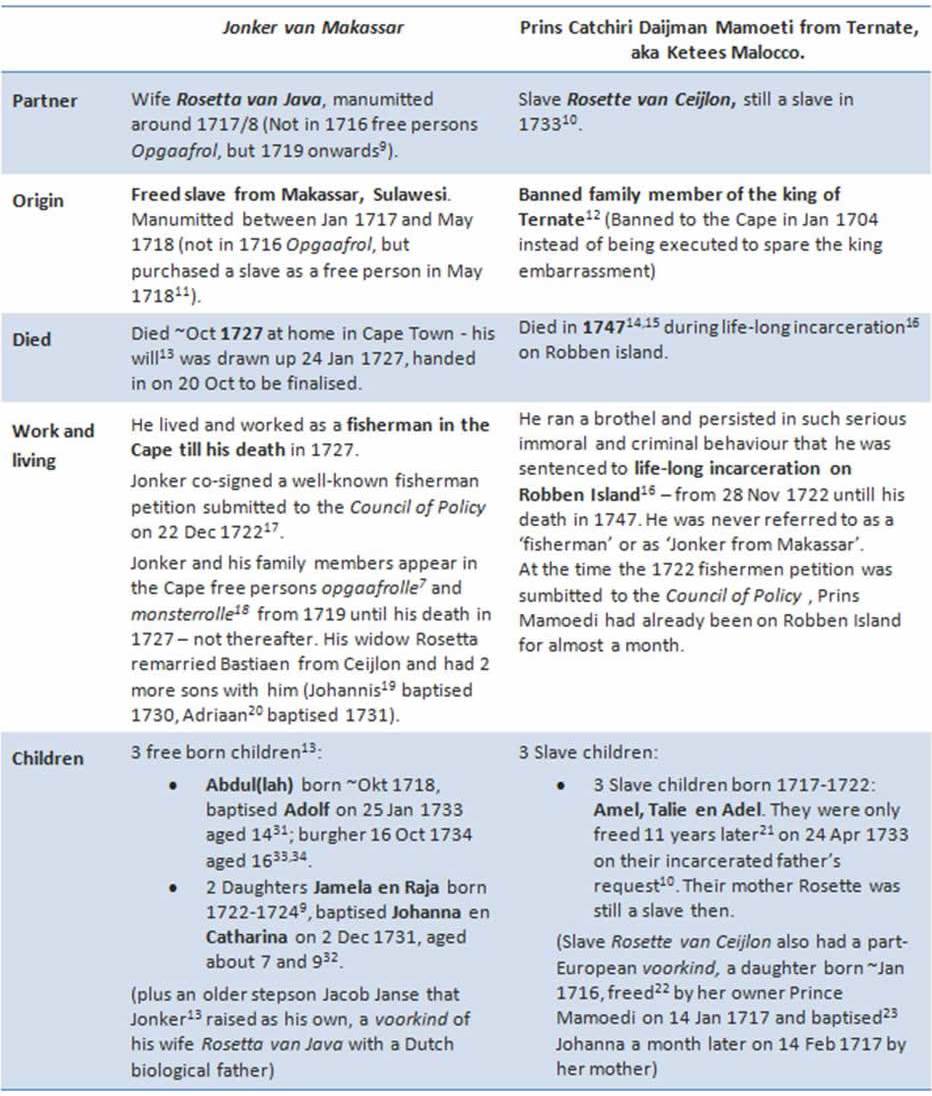

• 1958: Genealogist dr. J Hoge1 unleashed much controversy by claiming that Adolph was the son of free slaves Jonker van Makassar and Rosetta van Java. His cited documents indicated that he also believed Jonker van Makassar to have been the same person as banned Prince Catchiri Daijman Mamoedi from Ternate (aka Ketees Malocco). No explanation for this conclusion was given however

• 1965-6: Dr A.H. Jonker2 and dr. C. Pama supports German descent

• 1959-1986: Malherbe3 (1959) and Heese & Lombard4 (1986) support Jonker van Makassar as Adolph’s father

• 2013: Mansell Upham5 supports dr. Hoge’s 1958 claims

Recently two genealogists Martina Louw (descendant of Adolph Jonker) and Jaco Strauss (administrator of the FTDNA Cape Dutch Y-DNA Stamvader Project) combined modern DNA technology with rigorous documentary research, to establish the truth about stamvader Adolph Jonker’s origin. Their findings have been published in a comprehensive article Die Herkoms van Stamvader Adolph Jonker (1718-1779)6 in Familia. The following information is a summary of this article.

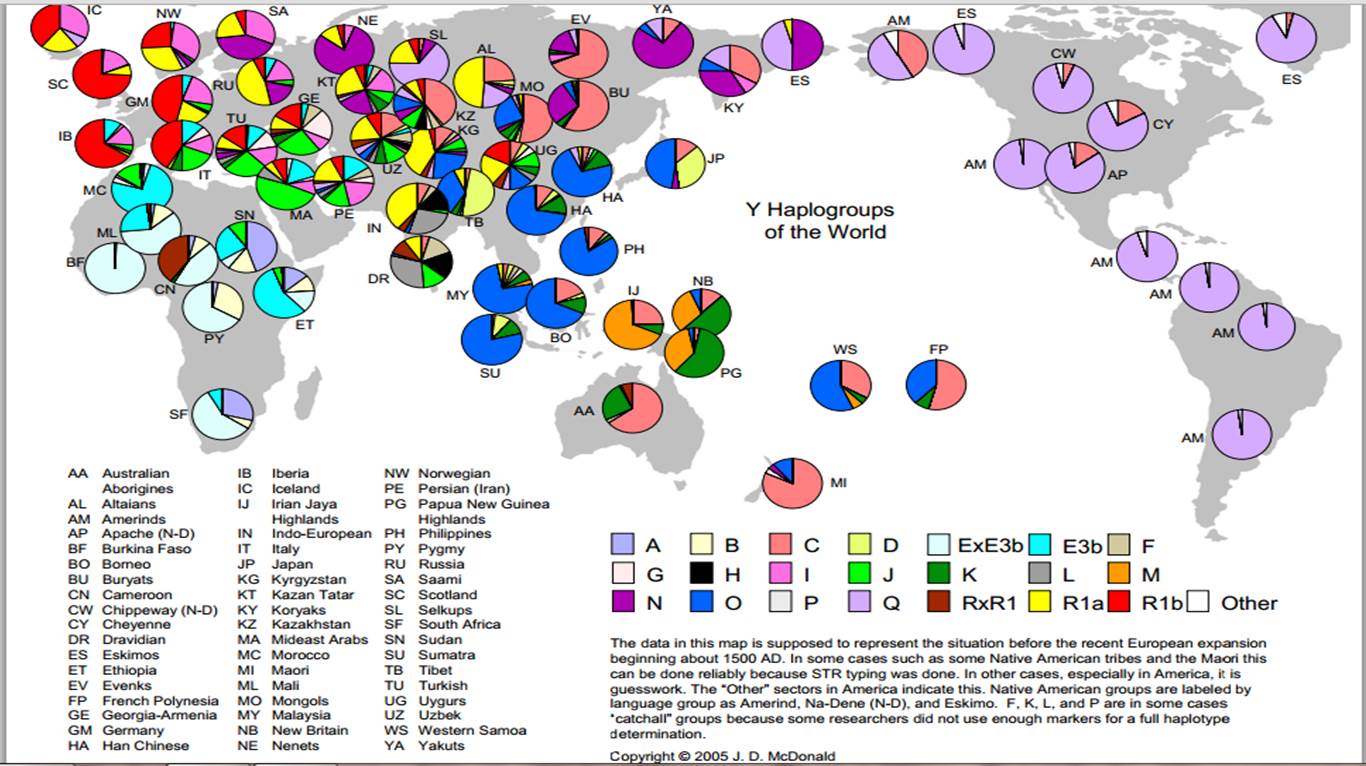

The researchers approached two male descendants of Adolph Jonker who agreed to join Jaco’s Cape Dutch Y-DNA Stamvader Project7 and have their Y-DNA tested in support of Jaco and Martina’s archive research. One of them is Martina Louw’s cousin Hennie Jonker, and the other dr. Koos Jonker, half-brother of poet Ingrid Jonker, and son of dr A.H. Jonker2. Their Y-DNA identified the haplogroup of their common patrilineal ancestor Adolph Jonker as well as the male ancestors before him in this direct line. Results showed that they both belong to a very rare subhaplogroup of haplogroup K that originated in south-east Asia.

Adolph Jonker is thus the first Afrikaner stamvader whose non-European patrilineal roots have been confirmed by Y-DNA analysis.

More information about haplogrop K and other Y-DNA haplogroups, as well as a graphic representation of their spread throughout the world can be found at DNAeXplained8 - as illustrated by this map:

Rigorous archive research also established conclusively that his parents were indeed the free slaves Jonker van Makassar and Rosetta van Java, but that Jonker van Makassar was definitely not the same person as the banned Indonesian Prince Catchiri Daijman Mamoedi from Ternate (aka Ketees Malocco). They were indeed different people with very different values and lifestyles, as illustrated in this table:

It could not be established with certainty when Jonker van Makassar and Rosetta van Java came to the Cape. We do know that Jonker required a Portuguese-Dutch translator in order to draw up his will. This is not surprising since Makassar in Sulawesi had been a major Portuguese trade centre until the Dutch took over in 1667 and families (many of nobility) heavily involved in Portuguese trade, had to flee or were forcibly relocated to other parts in the Dutch empire24.

Considering that he was called “Jonker” which was a Dutch form of address for a nobleman or son of a nobleman25, it is quite possible that Jonker’s family could have suffered this fate, resulting in him eventually being enslaved and taken to the Cape. This is of course speculation.

While most freeblacks were very poor26, soon after being manumitted Jonker was able to own a fishing boat and purchase slaves of his own. In his 1727 estate he left 4 slaves to serve his family members. He was without doubt very hardworking, but his business acumen, ambition and will to improve his family’s lifestyle could perhaps also be an indication of a privileged prior life.

We know from the first two wills27,28 of freeblack woman Rosetta van Bengal (1939 and 1947), that Jonker’s wife Rosetta van Java/Boegies was Rosetta van Bengal’s owner prior to her manumission, and that they had become such close friends that Rosetta van Boegies’s children were named in these wills as beneficiaries. In 1742 Adolph Jonker stood surety to enable Rosetta van Bengal’s husband Aron van Balij to free his slave Corydon van Bengal29.

Adolph Jonker was the eldest child of free slave muslim fisherman Jonker van Makassar and his wife Rosetta van Java, and would have been known as Abdul(lah) for the first 14 years of his life. He would have attended the Cape school in which Adolph Hofman30 was appointed teacher in 1723. It seems as if Adolph Jonker was a bright pupil and Adolph Hofman an inspiring teacher and mentor, considering Adolph Jonker’s later choice of career – teacher and koster of the Drakenstein congregation. He may even have been named after his teacher and mentor when baptised in 173331.

Adolph’s life was not without sadness, he lost his father Jonker van Makassar at the tender age of 913, and 4 years later aged 13 he also lost his mother Rosetta van Java9.

On 16 Oct 1734 Adolph Jonker became a burgher of Drakenstein33 aged 16. (It was a requirement that men register within 6 weeks of turning 1634, thus we know he would have been born between 4 Sept 1718 en 16 Oct 1718.)

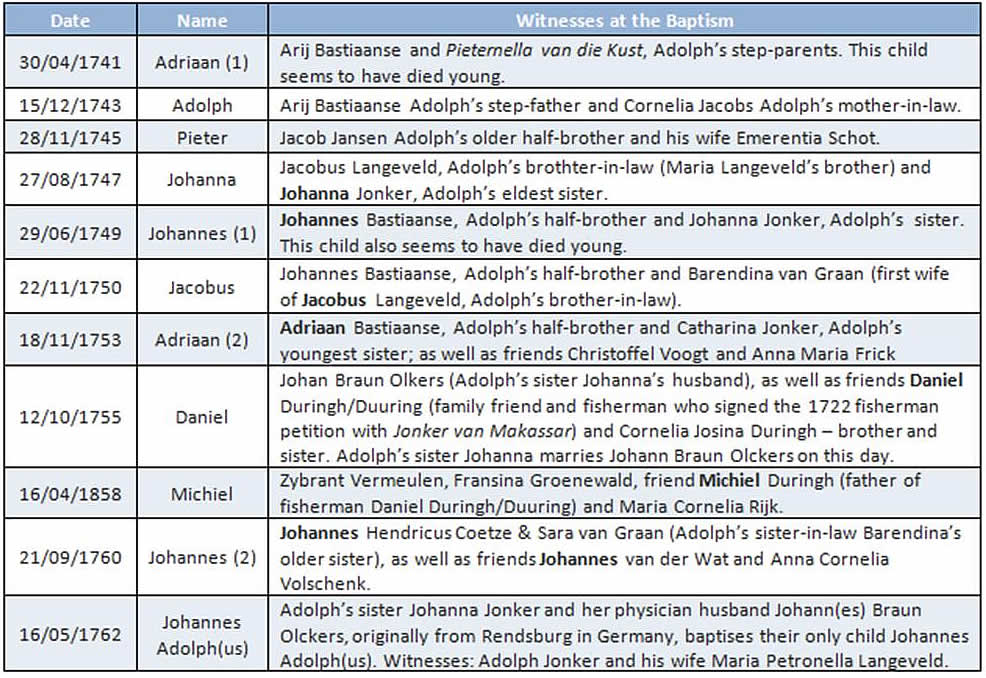

Six years later on 26 June 1740, Adolph married35 Maria Petronella Langeveld, daughter of Pieter Pietersz Langeveld and Cornelia Jacobs. They had 10 children, all but the first born baptized in Drakenstein where Adolph was appointed teacher and koster on 20 June 174536.

The children were named after family members, close friends and significant people in their lives, often signing witness to the baptisms. These baptismal records expose the close bonds that continued to exist between Adolph and various friends and family members, including his older half-brother Jacob Jansz, his sisters Johanna and Catharina Jonker, his younger half-brothers Johannes and Adriaan Bastiaans, and his step-parents Arij Bastiaans and Pieternella van die Kust(Kaap)– as illustrated in this table:

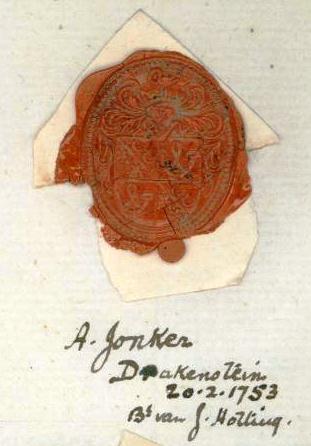

We do not know what Adolph Jonker did for a living between 1734 and 1745, but he was allowed to wear a sword which was a rare privilege at the time, and used a wax seal with strong Germanic traits to seal important documents. There is a wax impression of Adolph’s seal as used on 20.2.1753 in the Government Archives in Cape Town - seen in the photo below:

Adolph retired as teacher in Drakenstein after nearly 17 years on 5 May 1762. Apparently few teachers held their positions this long in those days. It seems he gave up teaching in order to become a farmer on pieces of land he had purchased37. At the time of his death he owned 130 goats, 15 cattle and a horse. He continued to be koster until his death in 177938.

Adolph was fluent in Dutch and German, and was also well-read. Although books were scarce in those days, he owned 20 on a variety of subjects, as well as 2 bibles. By all accounts he was an excellent teacher, a loyal friend and a dedicated familyman. In spite of his lowly freeblack background, he became a respected member of the Cape community and progenitor of the South African JONKER family.

Adolph Jonker is the first Afrikaner stamvader whose non-European (Indonesian) patrilineal roots have been established by archival research and confirmed by Y-DNA analysis.

Since traditionally South African Stamvaders are considered to be the first known male progenitor in each patrilineal line that settled at the Cape. Now that it has been established with certainty that Adolph Jonker’s father was Jonker van Makassar, it is expected that Jonker van Makassar will carry the title of Jonker Stamvader in future.

References and Sources:

1 HOGE, dr J., 1958. Bydraes tot die genealogie van ou Afrikaanse families; verbeterings en aanvullings op die Geslacht-Register der Oude Kaapsche Familiën. Amsterdam: A. A. Balkema.

2 JONKER, dr. A.H., 1965. Die stamvader - Adolph Jonker (I). Familia 2, 1965.

3 MALHERBE, DF du T, 1959. Driehonderd Jaar Nasiebou - Stamouers van die Afrikanervolk. Stellenbosch: Tegniek.

4 HEESE, J.A. & LOMBARD, R.T.L., 1986-1992. Suid Afrikaanse Geslagregisters. Pretoria : Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing.

5 UPHAM, M., 2013. Uprooted Lives (UL28): God’s Slave and the Afrikaner ‘Hearts of Darkness’ – Abdullah alias Adolph Jonker c.1707-1779.

http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/remarkablewriting/UL28_Jonker.pdf (as on 24/11/2013).

6 LOUW M. & STRAUSS J. (2015), Die Herkoms van Stamvader Adolph Jonker (1718-1779), Familia-52 2015 no 2.

This original comprehensive article is available to download in pdf format at

http://www.cdbooks-r-us.com/freebies.php

7 STRAUSS J. FTDNA Cape Dutch Y-DNA Stamvader Project: http://familytreedna.com/public/CapeDutch/default.aspx?section=goals

(as on 22/02/2015)

8 MACDONALD J.D. 2005, Y haplogroups of the World. http://dna-explained.com/2013/01/24/what-is-a-haplogroup/ (as on 26/02/2015)

9 HEESE H., Opgaafrolle for Cape Town and District (1719-1735). Cape Town Archive.

10 Resolutions of the Council of Policy of the Cape of Good Hope (11 Feb. 1733) C. 91, pp. 108-117.

11 SHELL R. Slave Transactions 1658-1731

12 LEIBBRANDT H.C.V. (1896). Precis of the Archives, Letters Received 1695-1708, no 282, p512, of 03/01/1704 and no 276, p437 of 01/02/1704. Kaapstad: W.A. Richards & Sons

13 Will (1727): CJ 2604:05 Jonker, van Maccassar. Cape Town Archive.

14 WORDEN N. & GROENEWALD G. (Editors) 2005, Trials of Slavery: Selected Documents Concerning Slaves from the Criminal Records of the Council of Justice at the Cape of Good Hope, 1705-1794. Kaapstad: Van Riebeeck Society.

15 DEACON H., (editor, 1996). The Island: A History of Robben Island, 1488-1990. Kaapstad: David Philip Publishers.

16 Resolutions of the Council of Policy of the Cape of Good Hope (24 Nov. 1722): C 61, pp 27-34.

17 Resolutions of the Council of Policy of the Cape of Good Hope (22 Des 1722): C. 62, pp. 22-35.

18 Bundle VC 50 – Monsterrollen – Vrije Lieden : 1726 – 1733. Cape Town Archive.

19 DRC Cape Town baptism: Rosetta and Bastiaen van Ceijlon’s son Johannis (24/09/1730)

20 DRC Cape Town baptism: Rosetta and Bastiaan van Ceijlon’s son Adriaan (14/01/1731)

21 Slave Manumission - Obligatiën, Transporten van Slaven, Vrijbrieven: CJ 3083 (1733). Cape Town Archive.

22 Slave manumission: Slave Johanna van der Kaap, ID nr 3252, aged 1 (14 Jan 1717). Cape Town Archive Court of Justice 3074, at http://www.Ancestry24.com (as on 17/08/2013).

23 DRC Cape Town baptism: Slave Rosetta from Batavia baptises her manumitted daughter Johanna (14 Feb. 1717).

24 WARD K., 2009. Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. USA: Cambridge University Press, pp 196.

25 VAN DER SIJS N. ,2010: Jonker (Aanspreektitel voor adelborst) http://www.etymologiebank.nl/trefwoord/jonker (as on 23/02/2015)

26 GILLIOMEE H., 2004.1731. De la Fontaine Report: “Vrijswarten, of ex-bandieten sijn doorgaans arm, veele bestaan van visschen”

27 Will (1739): CJ 2609:06 Rosetta van Bengaelen. Cape town Archive.

28 Will (1747): CJ 2658:48 1747; MOOC 7/1/10 - 37. Rosetta van Bengale. Cape town Archive.

29 LEIBBRANDT H.C.V. (1896). Precis of the Archives, Requesten (Memorials)1715-1806:1742, no32.

30 Resolutions of the Council of Policy of the Cape of Good Hope (21 Sept. 1728) Footnote [5].

31 DRC Cape Town baptism: bejaarde doop - Adolf (25 Jan 1733).

32 DRC Cape Town baptism: Rosetta’s daughters Johanna and Catharina (2 Dec 1731)

33 Eedboek, C. 678. (16 Okt. 1734).

34 Resolutions of the Council of Policy of the Cape of Good Hope (18 Okt. 1708): C.26, pp 107-109.

35 DRC Cape Town marriage: Adolf Jonker and Maria Pieternella Langveld (26 Junie 1740).

36 DRC Paarl, Minutes: 1731-1784.

37 LEIBBRANDT H.C.V. (1896). Precis of the Archives, Requesten (Memorials)1715-1806: 1752 no 75.

38 Estate: Adolph Jonker, Koster of Drakenstein: MOOC 8/17.51 (20 Feb 1779). Cape Town Archive.

- Hits: 39759